FOUL ODOR

UPPER MARKET GALLERY is thrilled to bring you FOUL ODOR: AN EXHIBITION ON SURVIVAL as part of a gallery takeover by Off Hours, a nomadic curatorial project led by Katherine Jemima Hamilton, Shaelyn Hanes, and Ebti. Together, they present artist-driven exhibitions that result from dialogue developed during studio visits, ongoing conversation, and collaborative writing practices.

Foul Odor is a group exhibition of works by Quinn Girard, Tuesday Iverson, Tajo McBurnie, Julio Rodriguez, Victor Saucedo, and Haley Summerfield that explores DIY and anti-establishment artmaking practices as a tactic for community survival. It is curated by Off Hours with a curatorial intervention by Joel Lithgow and Joseph Blake of This is a House Gallery. There is an artist shop with affordable and small-scale works by over fifteen artists. Inventory will be updated as the exhibition unfolds. Programming will be announced on a rolling basis. For additional information, email offhours.sf@gmail.com. Read the KQED review HERE. Full press release below.

opening reception: july 19, 6-9pm

duration: july 19 - august 31

open weekends from 12-3pm and by appointment - please look out for updates on Instagram

HALEY SUMMERFIELD

The Myth of the Thicket, 2024

Ceramic, glaze, epoxy, ribbon, beads, shell, wire

8 x 12 x .5 inches

$450

HALEY SUMMERFIELD

The Myth of the Thicket (Detail)

JULIO RODRIGUEZ

The limits of my own language, 2017-2024

Acrylic, paint marker, spray paint, collaged elements on canvas

36 x 60 inches

$3,000

TUESDAY IVERSON

Pennsylvania & Mariposa, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

18 x 14 inches

$650

JULIO RODRIGUEZ

Desahogar, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

30 x 24 inches

$700

VICTOR SAUCEDO

Vamos Al Norte, 2024

Glazed earthenware, found wood

10 x 17 inches

$850

TAJO MCBURNIE

Best Comfort Space Heater 1, 2024

Oil stick, oil pastel, oil paint, acrylic, plaster

40 x 30 inches

$2,500

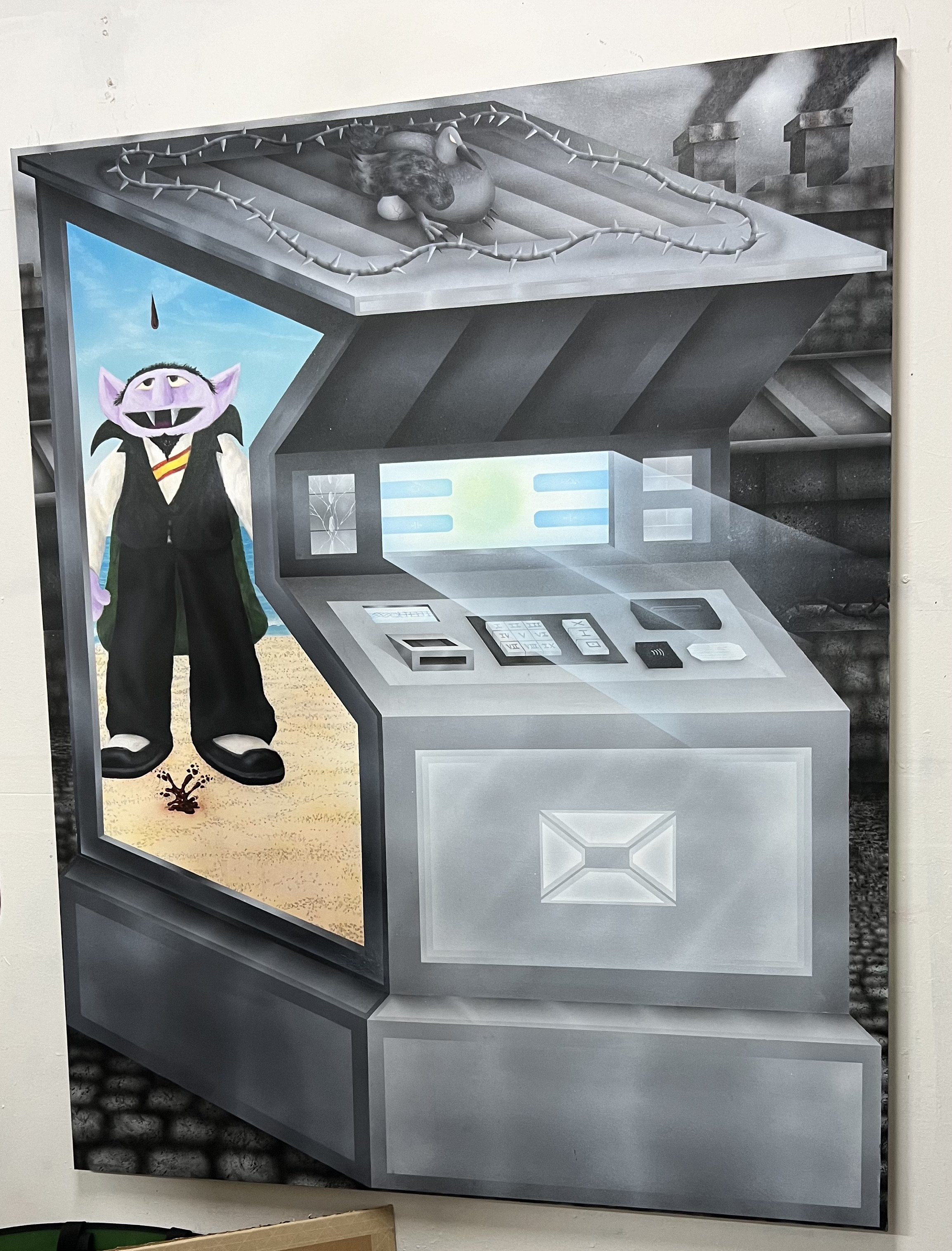

JULIO RODRIGUEZ

Hush, 2024

Single channel video

5:11

NFS

TUESDAY IVERSON

Heaven's Gate, 2024

Ceramic

8.5 x 7.5 inches

$275

TAJO MCBURNIE

Arcane Egg, 2023

Oil stick, oil pastel, oil paint,

plaster

40 x 35 inches

$2,500

TUESDAY IVERSON

Portrait of Phoebe, 2023

Ceramic, underglaze, gold luster

5.5 x 5 x 12 inches

NFS

VICTOR SAUCEDO

NOMEX, 2023

Glazed earthenware, cement, wig

12 x 11 x 11 inches

NFS

QUINN GIRARD

Town Square, 2024

Acrylic on canvas

60 x 40 inches

$3,000

QUINN GIRARD

Cart, 2024

Metal, papier mâché, enamel, foam, paper

51 x 20 x 84 inches

$5,000

QUINN GIRARD

Camera, 2020

Plastic, papier mâché, acrylic, wood, plaster

12 x 6 x 6 inches

$1,500

TAJO MCBURNIE

Hangers, 2024

Plaster, latex house paint, oil paint

20 x 16 inches

$1,200

TAJO MCBURNIE

Egg, 2023

Plaster, latex house paint

36 x 30 inches

$2,200

SAN FRANCISCO—50 years ago, San Francisco was a mess. It was 1974. The city was fumbling its response to the brutal and racially charged Zebra Murders. Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation Army robbed a bank in the Sunset District. BART had just opened and its long, multi-year construction tore up massive parts of the city. Tourism plummeted and thousands from the middle class were fleeing to the suburbs. 50 years later, the city is clawing its way out of yet another doom loop.

Who is left in times like these? The rich who can buy houses in the privacy of the hills, the poor who can’t afford to leave. Die-hards, old-timers, lifers. Artists. 1974 was the time of Bay Area conceptualism, second-wave feminism, performance and video art, happenings. Peter Voulkos made clay into an art form at UC Berkeley. Lynn Hershman Leeson commissioned site-specific artworks across the city as part of the Floating Museum. Dozens of artist-run centers were formed that became full-blown institutions—a handful are still kicking. When the city’s population dwindled, the artists swarmed in, fueled by the energy of the 1960s and in defiance of New York’s newly crowned jewel of the art world.

For many of us, surviving in San Francisco requires ingenuity, grit, fearlessness. The sidewalks are covered in stomach-churning substances, the buses are crammed with tired, sweaty commuters (and more sticky substances). Half the city’s weight is made of ugly, discarded, bad-smelling things. You have to embrace it. The artists in Foul Odor embrace the city’s grime as something beautiful, poetic even. Following in the DIY and anti-establishment legacy of the artists who inhabited San Francisco in the 1970s, Quinn Girard, Tuesday Iverson, Tajo McBurnie, Julio Rodriguez, Victor Saucedo, and Haley Summerfield—intentionally or unintentionally—work in traditions that tie back to Peter Selz’s infamous Funk show at BAMPFA in 1967. These young sculptors and painters consume comic books, video games, street art, and the city around them to make work that is foul and tender. Selz famously defined Funk Art as “hot rather than cool; it is committed rather than disengaged; it is bizarre rather than formal; it is sensuous; and frequently it is quite ugly and ungainly.” The works in this exhibition are—frankly—ugly, ungainly, odd, grim, nasty. They are also mesmerizing, gripping, magnetizing, fascinating like an unsightly creature from another world, conspicuous and unforgettable like hot garbage in the street. You can’t look away or unshake its nauseating scent. Maybe persistence is how these ideas, these styles, have clung to artists through time—it can take more than proverbial hand soap to scrub out an exceptionally foul odor.

Survival also requires communities to come together, sharing and redistributing resources, finding new ways to work together and hold each other up. We were unsatisfied by our authoritarian role as curators making declarations about a group of artists and their relations as Selz did more than 50 years ago. As an antidote, we’ve invited the Oakland-based artist collective This Is A House Gallery (who typically host exhibitions in their living room) to intervene with the exhibition halfway through its run, offering insight into how another group of artists might define or confuse what we frame as Funk’s influence. Requesting only that they do not “damage the space or the art,” the invited curatorial group has free reign over the DIY art space to decide what legacies they’d like to unearth, reject, or create. Just as the counter-culturalists of the 1960s and ‘70s refused their market centers, their mainstream, this generation of artists and organizers now pushes against those established legacies and organizations that have been historicized through institutions. In perpetuating this cycle of rebellion from inside San Francisco’s current doom loop, these artists create a path for future generations to step into the sequence, leaving a legacy of Funk—oh, excuse me, a trail of foul odor behind them.